Winter 2013

|

TOWER

13

where Amie, not particularly keen on teaching at that

point, was living and working after graduation.

“A friend of mine from Kutztown had associates

who were working in Saudi Arabia, teaching English

as a foreign language,” she said. “When they came

back to visit I was inspired by their stories and by

their experiences.”

She did some research and in 1983 started work on

her master’s in Teaching English as a Foreign Language

at American University in Cairo.

Amie had always done well in writing classes at KU.

While studying in Cairo, she began writing stories for

American newspapers. She wrote about horses (Amie

owned four, one being a purebred Arabian) and Bedouin

(nomadic Arab tribes) culture.

“My creativity shifted from canvas and sculptures

to writing,” she recalled.

She also started teaching English classes to native

Arabic speakers at the university, even after graduating

in 1986, and at the U.S. Embassy. In 1987, through an

American company, Telemedia, Amie was teaching

English and developing curriculum for cadets in the

Egyptian Air Force Academy in Bilbeis.

Two years later, she was in Bahrain, now a contribut-

ing reporter for the Associated Press.

A year later, Saddam Hussein’s forces rolled into

Kuwait, and the gravity of war exerted its inexorable

pull on Amie’s life and career.

“I didn’t ask to get involved in conflict; it just hap-

pened,” she said. “My focus at AP shifted from banking,

finance and culture, to flak jackets, chemical suits and

gas masks. The scary part were incoming Scuds (mis-

siles). Many were landing in Bahrain or in the waters

between Bahrain and Saudi Arabia.”

Amie points out that while “the Gulf War only lasted

about 100 days, the seven-month build up led to the

largest stress.”

“The tension was more unnerving than the war

itself,” she remembered. “During the war, you’re so

busy. When the conflict finally came to a head it was

almost a relief.”

Nonetheless, post-conflict Iraq was action-packed,

she said, with threats from Saddam, border issues, oil

well fires and oil smuggling.

Her employers varied over the next few years: she

covered Kuwaiti reconstruction for a U.S.-based think

tank, Pasha Publications; she set up and managed a

Kuwaiti news bureau for United Press International

(UPI); Deutsche Presse-Agentur hired her twice to

cover events from Kuwait; and she joined Platts, the

energy division of McGraw-Hill Financial in 2000.

That’s in addition to freelancing for CNN, CNN

International, CBS “60 Minutes,” CBS Radio and

Washington Newsdesk.

During the 2003 Iraq War, she was a unilateral

reporter, as opposed to one embedded with a military

unit. She had more freedom, but ran far greater risk.

At times, Amie traveled with a Kuwaiti oil well

firefighting team, whom she describes as wonderful

friends who would have laid down their lives for her.

It was with them, in Southern Iraq, after the men had

cleared a path through a minefield, where she found

herself scrambling for cover across barren ground when

unknown adversaries opened fire on them.

She still remembers sleepless nights in Iraq when

rocket attacks drove her and others into bunkers.

In 2011, Amie decided to broaden her horizons,

becoming strategic communications advisor for USAID

in what is called the U.S. Regional Platform South,

Kandahar, Afghanistan. Her tasks included helping

mentor government organizations to create broadcasts

for anti-narcotic efforts and for peace and reconciliation

among tribes.

Gender violence, she said, was prevalent, and she met

women who were battered and otherwise abused.

“Part of my job included mentoring Afghan nongov-

ernment organizations to secure U.S. government funds

to further media and gender development,” she said. “I

ended up creating the first-ever gender strategy for

Southern Afghanistan.”

Radio in a box (RIAB) kits, used to set up a complete

broadcasting station, proved useful at penetrating

ancient walls and reaching geographically isolated

populations.

“The women we worked with were always under

threat,” she said. “Some carried weapons. They were

cloistered. But radio is a driving force. It’s the glue that

keeps society together. It makes them feel like they’re

bonded. They can be miles apart but can connect via

cell phone to a radio program and still be anonymous.”

Meanwhile, the war continued in fits and spurts,

with periods of daily and nightly shelling, and relatively

peaceful stretches in between. Nobody was truly safe.

“It was always hard to hear news that your colleagues

were involved in accidents or hit by an IED (improvised

explosive devise),” she said.

In September 2012, Amie left USAID and returned

to Kuwait, her headquarters for much of the past 25

years, where she has been doing stories for Platts.

How does she do it? How does she handle the stress

of conflict and a deadline-intensive industry?

“Wherever I set up my home and my office, home

always becomes my retreat,” she said. “I come back to

decompress, have some downtime and recharge my bat-

teries. I believe that my years of practicing yoga have

helped me cope and maintain stability while working in

conflict zones. I love taking care of animals. That is the

domestic side of me. I had horses when I was in Egypt,

and I have my cats with me now. ”

Amie is happily married to her career.

“My work is my life and I like that. I get up like a

fireman every day, ready to do the job.”

Miriam Amie

1976

Graduates from

Kutztown University

with a degree in

art education.

1983

Moves to Cairo

to work on a degree in

Teaching English as a

Foreign Language.

1989

Becomes a contributing

reporter for the

Associated Press

.

1990

Iraq invades Kuwait.

Amie reports for

CNN and CBS

during the war and the

post-war period

.

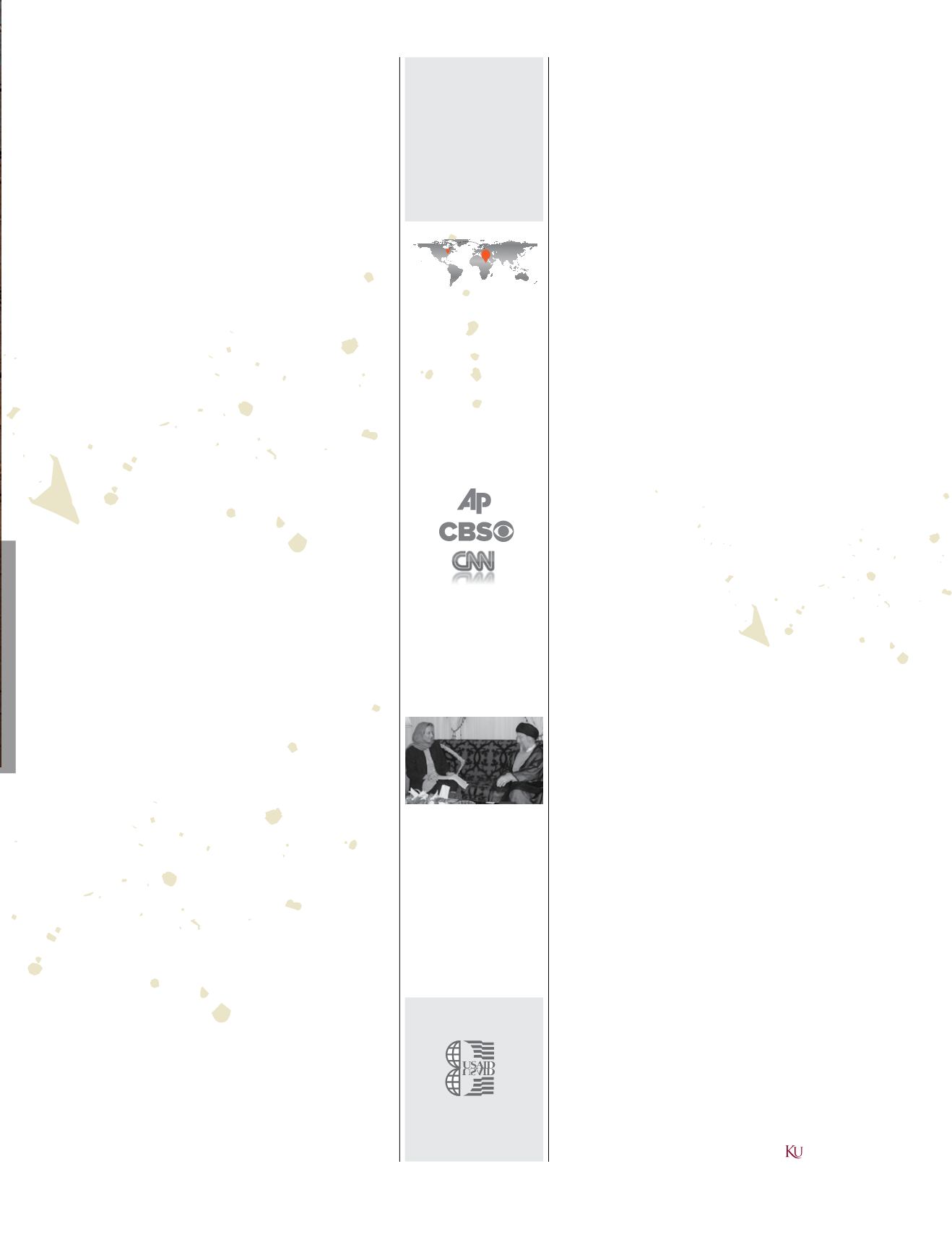

2000

Amie interviews Ayatollah

Sayed Mohammed Baqir

al-Hakim in Kuwait.

He was one of the

most influential Shia

Muslim spiritual leaders

with millions of followers

in Iraq and Iran.

2011

Becomes a

strategic

communications

advisor for USAID

.

2012

Returns to Kuwait.